Chikungunya in China: How a “Forgotten” Arbovirus Found the Perfect Storm

11 August 2025 | Monday | Analysis

Local health authorities reported thousands of cases within weeks; by early August, figures converged around the several-thousand mark, with some reports topping 8,000 as case-finding intensified.

This is not business as usual. Until now, China’s chikungunya cases were largely imported, with little evidence of sustained local transmission.

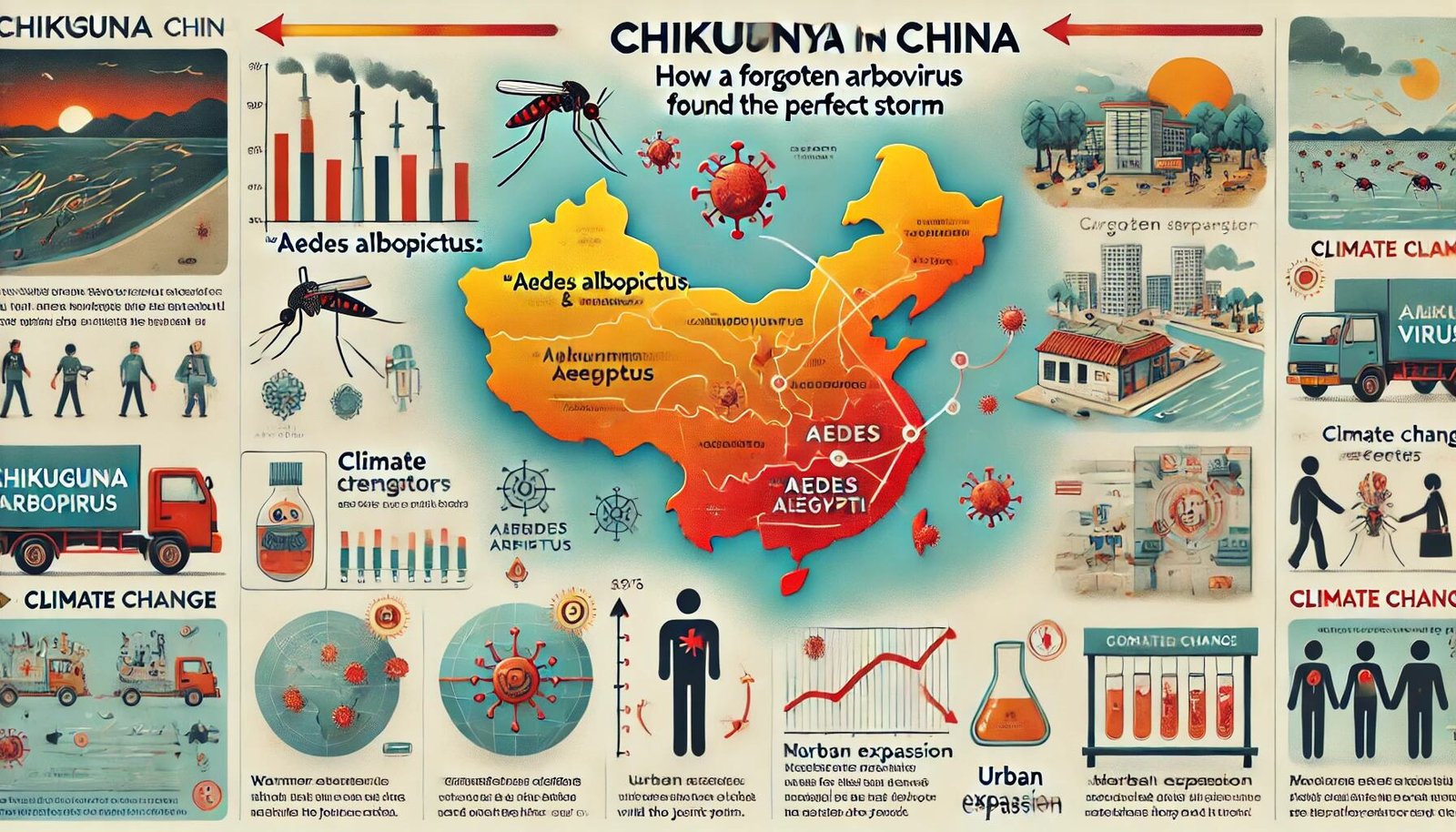

For those outside the public health field, chikungunya (CHIKV) is a mosquito-borne virus, spread primarily by Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. It causes high fever and often excruciating joint pain. Rarely fatal, it can still be profoundly debilitating, with some patients suffering lingering joint pain for months. The disease can overwhelm primary care during peak transmission periods and sap productivity long after the fever subsides. The urgent question is why this outbreak has erupted in southern China now—and what it signals for the region’s future risk landscape.

The Spark: Timing, Vectors, and a Weather-Exposed Megaregion

Three dynamics converged in Guangdong this summer:

1) The right mosquitoes in the right place. Aedes albopictus is entrenched across much of China, while Aedes aegypti is more restricted to the south but still present. Climate models forecast further northward and westward expansion for these species, with southern China persistently high-risk. Chikungunya, like dengue, travels on the wings of these same mosquitoes.

2) A monsoon-fuelled breeding bonanza. Hot, wet weeks bring an explosion of breeding sites and accelerate mosquito development. Guangdong’s early-summer floods and heavy rains boosted vector populations just as imported introductions from Asia–Africa travel routes were likely to occur.

3) Viral seeding in dense, mobile cities. Foshan and the Greater Bay Area offer dense housing, fast logistics, and short-range mobility—ideal conditions for virus–vector–human contact chains. Once a critical number of viraemic individuals and high mosquito density coincide, local transmission can surge rapidly.

The Numbers (and Why They Vary)

As surveillance expanded, case counts climbed. By late July, there were nearly 5,000 confirmed cases, with 98% in Foshan. By early August, figures of 7,000–8,000 were being reported, with some estimates exceeding 10,000 as hospitals, clinics, and community surveillance flagged more cases. Variations in numbers reflect both the rapid growth of the outbreak and differences in confirmed versus probable case definitions.

The virus has already crossed borders. Hong Kong has reported multiple imported cases linked to Guangdong, while Taiwan confirmed its first imported case in early August. Given the volume of short-distance travel and trade in the region, this cross-border spread was inevitable—and points to the need for regional coordination.

The Response: Familiar Tools, New Frictions

Guangdong authorities moved quickly with vector-control measures: draining stagnant water, spraying insecticides (including via drones), and launching public education drives. Pharmacies were instructed in some districts to report fever-medicine purchases to enhance surveillance. Hospitals expanded testing, and fever clinics were mobilised to collect samples.

However, not all measures have been popular. A widely circulated incident saw officials enter a home at night to take children’s blood samples while their mother was at work, sparking criticism. Such actions, reminiscent of strict zero-COVID measures, risk undermining trust. For public health measures to succeed, transparent communication, clear consent protocols, and active community participation will be essential.

On the global stage, the U.S. has issued a Level 2 travel notice for Guangdong, advising travellers to take enhanced precautions. It also highlighted the availability of two licensed chikungunya vaccines in the U.S., signalling a significant shift in global preparedness—even if access in China is not yet on the table.

Why Chikungunya, Why Now? The Deeper Drivers

Climate and urbanisation. Rising temperatures shorten mosquito development cycles and the virus’s incubation period. Heavy rainfall increases breeding sites. Rapid urbanisation, particularly where water storage is common, creates countless larval habitats.

Immunity gaps. Unlike dengue, which has circulated enough in parts of Asia to offer some population immunity, China has had little historical exposure to chikungunya. With no pre-existing immunity, outbreaks can escalate quickly.

Human mobility. Guangdong’s deep links to domestic and international trade, tourism, and migrant-worker networks facilitate the silent importation of the virus.

Surveillance asymmetries. Chikungunya’s symptoms—fever and joint pain—can be mistaken for dengue or other viral infections. Without active testing, early cases may be missed, allowing transmission to gain a foothold.

Health System Impacts: The “Long Tail” of Pain

While chikungunya rarely causes death, its after-effects can last for months. Persistent joint pain can limit mobility, particularly in older adults and those with chronic conditions. This means more outpatient visits, specialist referrals, and lost workdays in industries from manufacturing to construction. Even if hospitalisations are low, a major outbreak can strain the healthcare system well beyond the mosquito season.

The Risk Horizon: From Guangdong to a Wider Southern Arc

Although Guangdong remains the epicentre, neighbouring provinces share similar risk factors—climate, urban density, and water storage practices. The flow of people will keep seeding opportunities for the virus. Hong Kong and Macao are already managing import risks, and Southeast Asia could see two-way transmission in the months ahead.

Globally, chikungunya is resurgent. In East and South Asia, the risk is now firmly seasonal, aligning with monsoon cycles and weather fluctuations.

Communication Pitfalls: Fear, Fatigue, and Trust

Two communication challenges stand out:

-

Over-correction from the COVID era. Heavy-handed measures may bring short-term gains but damage public trust.

-

Mixed messages on severity. While not typically deadly, chikungunya is far from harmless. Public messaging must balance urgency with reassurance.

Five Priorities for Action

-

Targeted vector control. Focus interventions on specific hotspots, using mapping and technology such as drones to identify and treat breeding sites.

-

Smart surveillance. Implement privacy-protected pharmacy reporting and integrate routine arbovirus testing into fever clinics.

-

Protect the vulnerable. Prioritise older adults, pregnant women, and those with pre-existing conditions for prevention measures.

-

Prepare for post-illness care. Equip clinics to manage long-term joint pain and encourage employers to support flexible recovery periods.

-

Coordinate across borders. Ensure rapid, routine information-sharing between Guangdong, Hong Kong, and Macao.

Industry’s Role: Diagnostics, Vaccines, and Vector Tech

Diagnostics. Multiplex tests that can distinguish dengue, chikungunya, and Zika will be critical in front-line clinics.

Vaccines. While mass vaccination in China is unlikely soon, targeted use for high-risk groups may be feasible in future.

Vector control technology. From drones to Wolbachia mosquito releases, new tools should complement traditional methods, with deployment guided by real-time vector and weather data.

The Rights Question: Doing Tough Things the Right Way

Public health emergencies challenge the balance between urgency and rights. Guangdong’s experience underscores the need for consent, clarity, and collaboration. Communities that feel respected and engaged are more likely to take the measures—covering water containers, allowing inspections, seeking early care—that stop transmission.

Beyond This Season: Building Arbovirus Resilience

The chikungunya surge is a stress test for China’s urban health defences. Lasting gains could include:

-

Year-round, data-led vector control units.

-

Integrated febrile illness testing in primary care.

-

Stronger public trust through transparent and respectful engagement.

What to Watch Next

-

Case trends – A slowdown in new cases in heavily targeted districts would signal progress.

-

Cross-border spread – Monitoring Hong Kong and Taiwan for secondary transmission after imported cases.

-

Refined protocols – Adjustments in Guangdong’s approach to balance control with civil liberties.

-

Vaccine uptake – Tracking whether more travellers seek vaccination as advisories spread.

Bottom Line

China’s chikungunya surge is not a local anomaly—it’s a warning. Climate-amplified vectors, dense urban exposure, and immunity gaps have created fertile ground for arboviruses. Guangdong’s response now faces a double test: bending the outbreak curve without breaking public trust. With focused control, humane surveillance, healthcare readiness, and cross-border cooperation, the worst can be contained. But the real victory will come if 2025 marks the year China shifts from reacting to anticipating in the era of emerging vector-borne diseases.

Most Read

- How Does GLP-1 Work?

- Innovations In Magnetic Resonance Imaging Introduced By United Imaging

- Management of Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma

- 2025 Drug Approvals, Decoded: What Every Biopharma Leader Needs to Know

- BioPharma Manufacturing Resilience: Lessons From Capacity Expansion and Supply Chain Resets from 2025

- APAC Biopharma Review 2025: Innovation, Investment, and Influence on the Global Stage

- Top 25 Biotech Innovations Redefining Health And Planet In 2025

- The New AI Gold Rush: Western Pharma’s Billion-Dollar Bet on Chinese Biotech

- Single-Use Systems Are Rewiring Biopharma Manufacturing

- The State of Biotech and Life Science Jobs in Asia Pacific – 2025

- Asia-Pacific Leads the Charge: Latest Global BioSupplier Technologies of 2025

- Invisible Threats, Visible Risks: How the Nitrosamine Crisis Reshaped Asia’s Pharmaceutical Quality Landscape

Bio Jobs

- Sanofi Turns The Page As Belén Garijo Steps In And Paul Hudson Steps Out

- Global Survey Reveals Nearly 40% of Employees Facing Fertility Challenges Consider Leaving Their Jobs

- BioMed X and AbbVie Begin Global Search for Bold Neuroscience Talent To Decode the Biology of Anhedonia

- Thermo Fisher Expands Bengaluru R&D Centre to Advance Antibody Innovation and Strengthen India’s Life Sciences Ecosystem

- Accord Plasma (Intas Group) Acquires Prothya Biosolutions to Expand Global Plasma Capabilities

- ACG Announces $200 Million Investment to Establish First U.S. Capsule Manufacturing Facility in Atlanta

- AstraZeneca Invests $4.5 Billion to Build Advanced Manufacturing Facility in Virginia, Expanding U.S. Medicine Production

News